One Group of Vessels from the Treli Burial Ground (11th-6th centuries BC)

Nino Akhvlediani, Irine SultanishviliMoambe, Georgian National Museum. Issue XI (57-B), გვ.56-81

Accepted: July, 2024

Published: December 2024

Keywords: Treli, Ceramic, Georgia, Early Bronze Age

Abstract

This article considers a group of ceramic vessels, dated from the 11th to the 6th centuries BC, which were discovered from the 1970s up to the present day at the Treli burial ground. The main part of the ceramic material comprises clay vessels characteristic of the Samtavro archaeological culture, on which, in some cases, the influence of cultural trends coming from the Near East are reflected. There are imported objects (an agalmatolite bowl) and forms made locally; however, the latter are completely alien to the local culture (zoomorphic vessels).

* * *

Ceramics make up the main part of the funeral inventory of the Treli cemetery1. An exception is a stone vessel – an agalmatolite bowl – that was found in burial no. 16.

Vessels were usually wheel-made. The pottery fabric consists of fine-grained clay, fired to black and gray. The surfaces are either polished or smoothed, but there are also vessels with rough surfaces. The ceramics are mostly decorated with geometric patterns. Ornaments were applied by pressing, cutting and polishing. In terms of purpose and forms, the earthenware is of many types. Below, we will consider several categories.

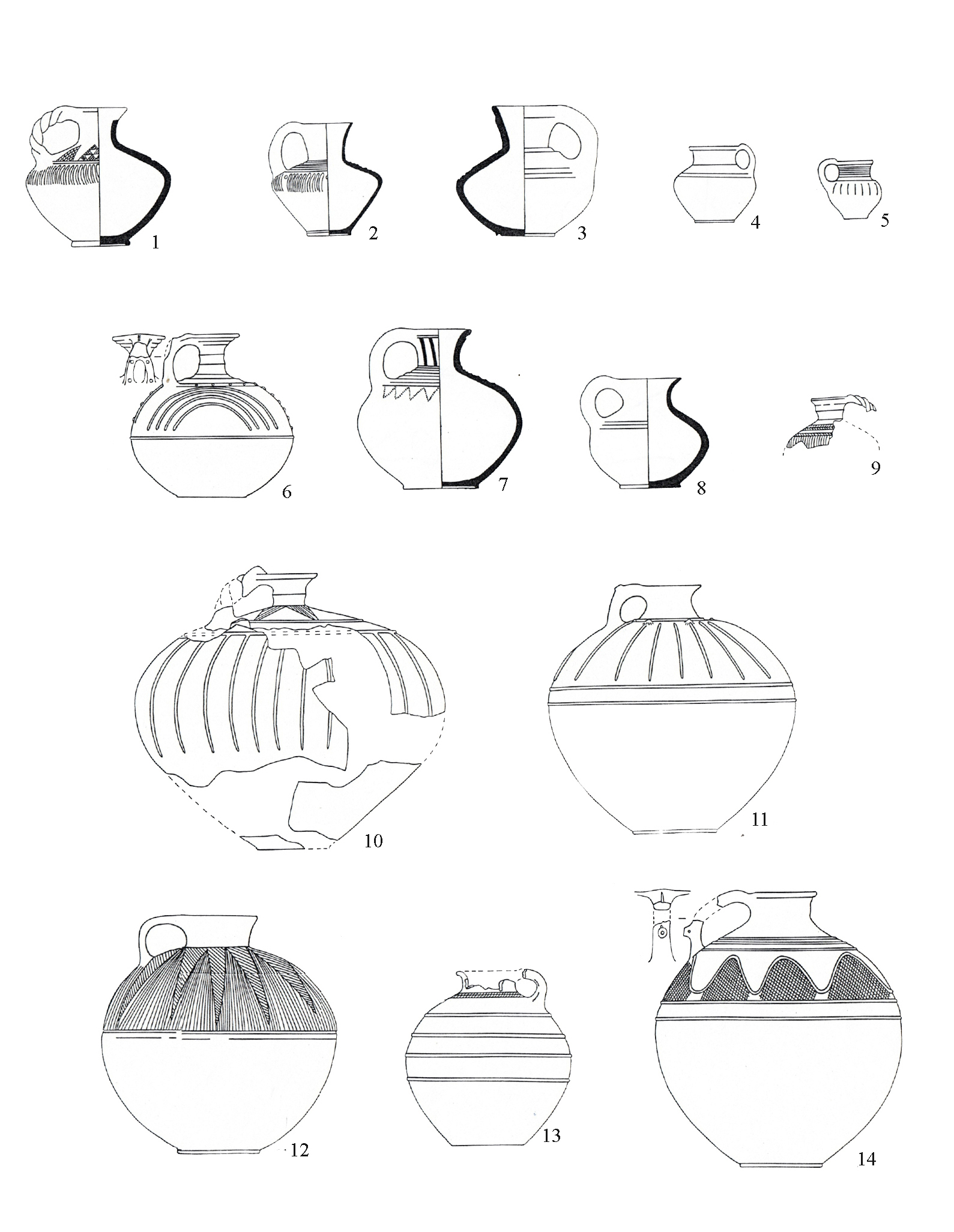

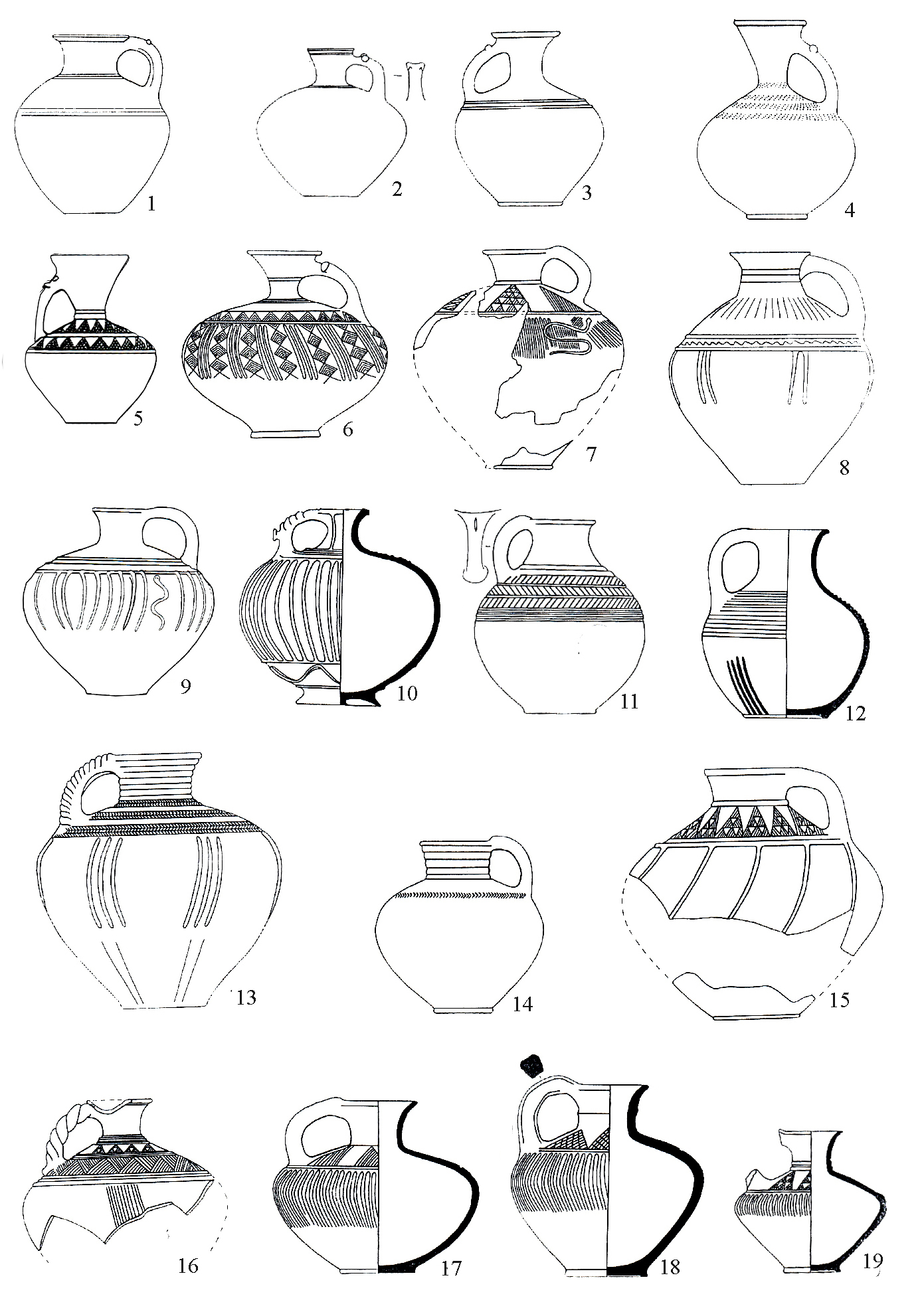

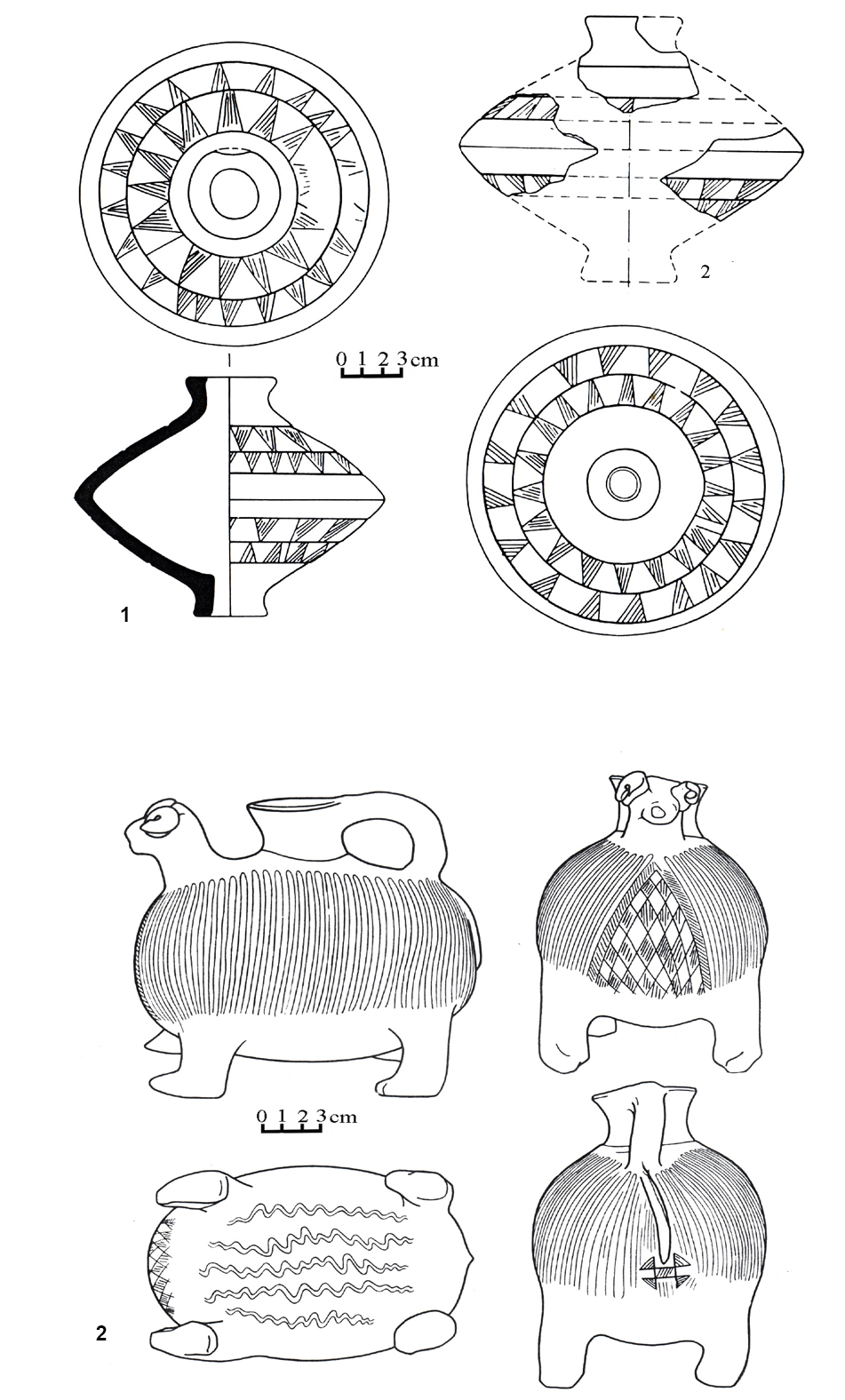

Jugs and Pitchers

Pottery of this type, found in burials dating to the 11th–6th centuries BC, differs from that of the preceding period2. In the 13th–12th centuries BC, vessels of this kind typically had a slightly elongated body of medium size, a narrowed throat at midsection, and a zoomorphic handle attached below the rim and on the shoulder. With the wider adoption of iron, however, their forms became more varied.In the 13th–9th centuries BC, the handles of the ceramics mentioned are zoomorphic, but since the 8th century, zoomorphic handles have become rare3. Pitchers from the same period often have spherical and large bodies, and the throat is relatively low and narrow. During the Late Bronze Age and Early Iron Age, most jugs and pitchers from Treli have a flat bottom or, in some cases, a low heel (Figure 1: 1-4, 7-8, 10, 11, 14; Figure 2: 3, 4, 6, 7, 12, 14, 15-19; Figure 3: 1,4,9). The pitcher from burial no. 7 differs from the others in its elliptical body, funnel-shaped neck, and highlighted, slightly expanding base (Figure 2: 7).

Jugs and pitchers from the Treli cemetery can be divided into two groups. In group 1, there are jugs and pitchers with zoomorphic handles (Figure 2: 1-6)3. Group 2 contains those units that do not have zoomorphic handles.

On the territory of Eastern Georgia, jugs and pitchers with zoomorphic handles are found at the settlement and cemetery of Treli (Abramishvili 1978: fig. 48520,521, 50533, 58594,596,600, 60612,613, 64651, 66664 ,665,666, 73 709); burials nos. 7 (Figure 2: 6), 66 (Figure 2: 1), 67 (Figure 2: 2), 109 (Figure 2: 3), 133 (Figure 2: 5), 134 (Figure 2: 5) etc; In the burials of Samtavro (Chubinishvili 1957: Tab.15455,585,626), Narekvavi (Apakidze 1999: Tab.I1, III38, IV56, XI129, XX247, XXII272, XXIII299, XXVII328, XXXI398, XXXVI508 1999: Tab.I1, III38, IV56, XI129, XX 247, XXII272, XXIII 299, XXVII328, XXXI398, XXXVI508; Apakidze 2000: ტაბ.XI585,584; XXIV6962000: Tab.XI585,584, XXIV696; Nikolaishvili, Gavasheli 2007: ტაბ.XV944, XXV1038, XXXIX1162, LV1317, LXII1386, LXVIII1432, LXXII1471,1469, LXXIII1489), Sapurtsle (burials nos. 1,2,3,4), Navtlugi (Koridze 1955:158-inv.3-50:18, Tab.XXX.1), Madnischala (Tushishvili 1972: pic.19,31,Tab.XXI), Sakdriskhevi (burials nos. 2,7), Gantiadi (Avalishvili 1974: ტაბ.IX), Grmakhevistavi (Abramishvili et al. 1980: pic.92147, 94152, 9615,105,187,188,189, 168423, 192518); At the settlements of Doghlauri (Gambashidze 1974: 137,Tab.I,4-5) and Khovlegora (Muskhelishvili 1978: ტაბ.XVI), and in Meghvrekisi (Kuftin 1949: Tab.XIII) etc. (Inner and Lower Kartli); They are found in Kakheti, at the Meli-Gele sanctuary (Pitskhelauri 1973: Tab.XXVIII-XXIX ), in Samtskhe – Zveli mound no. 2 (Gambashidze, Kvizhinadze 1982: Tab.XXIV.18) and at the Chitakhevi cemetery (unpublished).

Pitchers and jugs with zoomorphic handles were common during the 16th–6th centuries BC. The earliest pitcher comes from Zveli mound no. 2. This vessel is handmade and different in shape. It should be a prototype of the Late Bronze Age jugs. Jugs and pitchers of this type were found in the burials of Samtavro (burial nos.12, 26, 228, 294), belonging to an earlier stage of the Late Bronze Age, and in the cemetery of Madnischala (Tushishvili 1972: Tab. XXI116). It should be noted that Samtavro jugs and pitchers with zoomorphic handles have a refined shape. Pitchers and jugs with zoomorphic handles were widely distributed from the second half of the 15th century up to the 9th century BC. and were rarely found on the monuments of the 8th–6th centuries BC. On the territory of Eastern Georgia, these vessels are mainly characteristic of the so-called Samtavro culture (Abramishvili und Abramishvili 1995: 191-193). A relatively small number of them come from the Kakheti region, which is united in a circle of other archaeological culture. In the cemetery of Treli, from the 9th–8th centuries BC, jugs with twisted handles occur- burial nos.16 (Figure 1: 1,9; Figure 3: 7, 9, 10); 24 (Figure1:13; Figure 2: 16). These appear earlier in the Samtavro cemetery, from the 14th century BC -burial nos. 26 (1938), 175 (Akhvlediani and Sultanishvili 2010: Tab.I.4) and continue to be found until the 7th century BC – burial nos. 26 (1940), 72, 168, 301. In the cemetery of Treli, also from the 8th century BC, there are jugs with ledges on the handles – burial nos. 24 (Figure 1: 14), 119 (Figure 2: 10). From the same period as Treli burial nos. 16 (Figure 3: 6), and 46 (Figure 1: 6), also in Samtavro – burial no. 292, there are jugs with branched handles.

Group 2 includes a large number of jugs and pitchers, that, unlike group 1, do not have zoomorphic handles. The handles of the first group are attached under the rim; the handles of the second group are attached directly to the rim and on the shoulder line (the only exception is one jug from Treli burial no. 16 with a handle under the rim). These vessels have a spherical, elliptical, pear or biconical shape. They are decorated with various patterns. At the same time, jugs from burial nos. 7, 119 (Figure 2: 7, 9) have a relief image of a snake. Vessel from burial no.79 and a clay fragment from burial no. 242 have similar relief images. In the 14th–13th centuries BC, the relief image of a snake appears on the bodies of vessels in the Treli cemetery – burial no. 41 (Abramishvili 1978: Tab.XL627) and burial no. 138, and are rare throughout the Late Bronze Age and Early Iron Age.

Jugs and pitchers of both groups can be divided into separate subgroups according to specific characteristics. Despite some differences between the distribution areas of subgroups, as a whole, they are limited to Eastern Georgia, or more precisely, to Inner and Lower Kartli. At the same time, one of the variants of the second group has parallels not only in Georgia, but also abroad. These jugs have a very wide spherical body and a neck that is short compared to the body – burial nos. 24 (Figure 1: 10, 11, 14), 46, 247. Similar vessels originate from Armenia – Khrtanots, Golovino, and Akhtala (Morgan 1889: 58, Tab.17; Martirosyan 1954: Tab.XX,б,в).

In general, this type of pitcher is typical for Armenia. The chronological range of jugs and pitchers of the second group is the 8th-6th centuries BC.

Figure 1. Jugs and pitchers: 1-3, 7-9 – burial nos.16; 5 – burial nos. 6; 4,10,11,13,14 – burial no. 24; 6 – burial no. 16; 12 – burial no. 68

Figure 2. Jugs and pitchers: 1 – burial no. 66, 2 – burial no. 67, 3 – burial no. 109; 4,14 – burial no. 134; 5 – burial no. 133; 6,7 – burial no. 7; 8 – burial no. 79; 9,10 – burial no. 119; 11 – burial no. 40; 12,17-19 – burial no. 16; 13 – burial no. 49; 15,16 – burial no. 24.

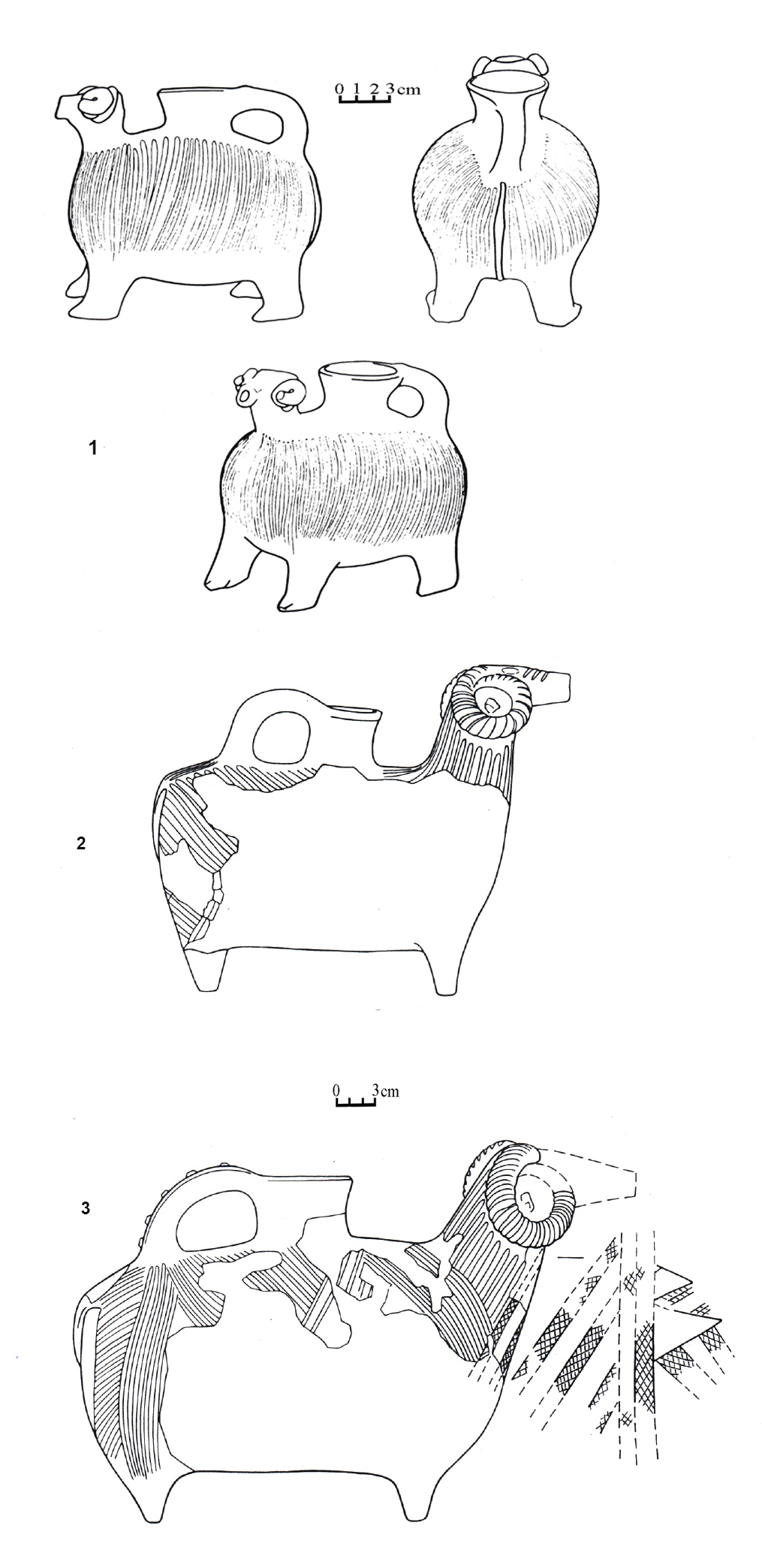

Figure 3. Jugs and pitchers from burial no. 16.

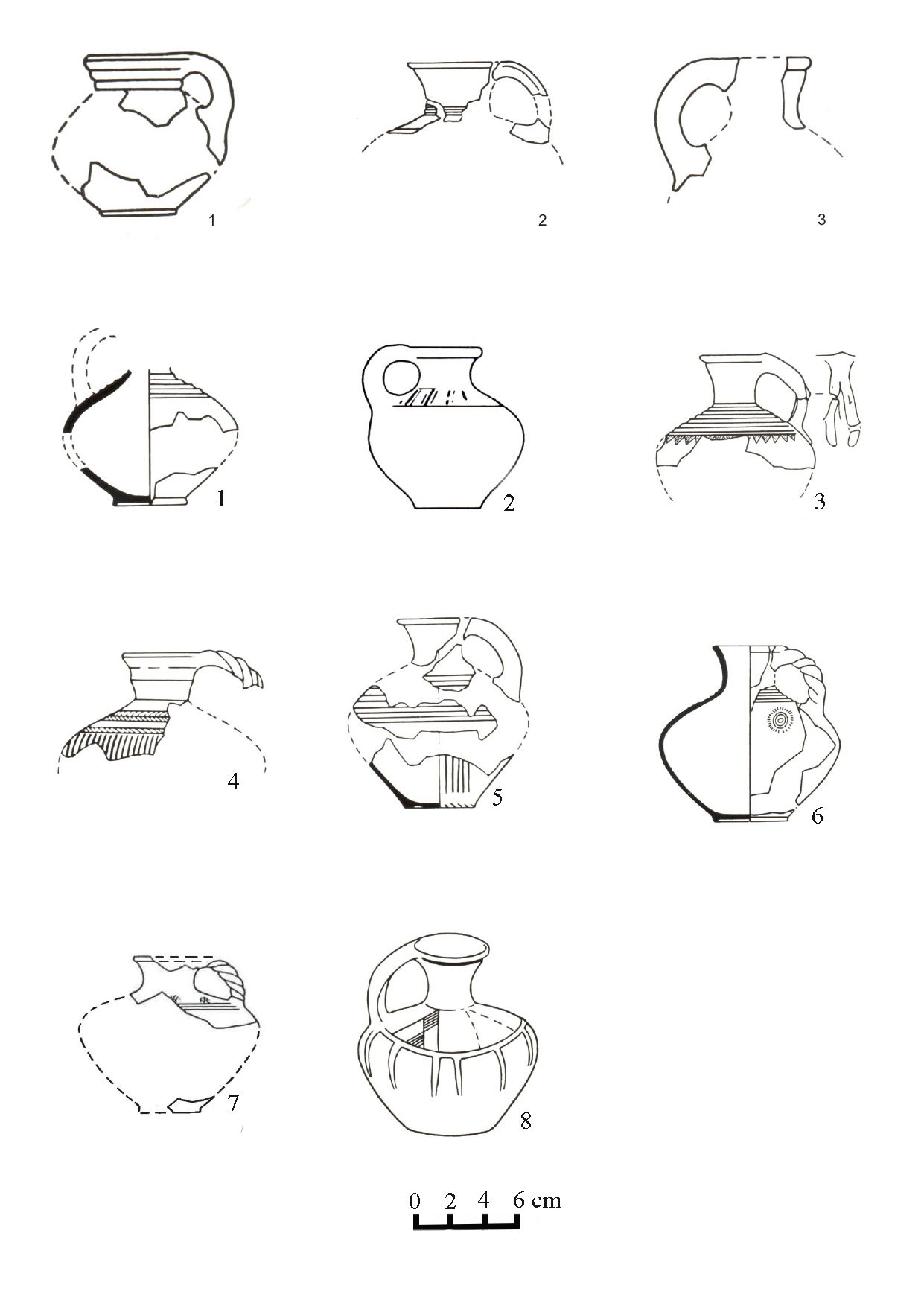

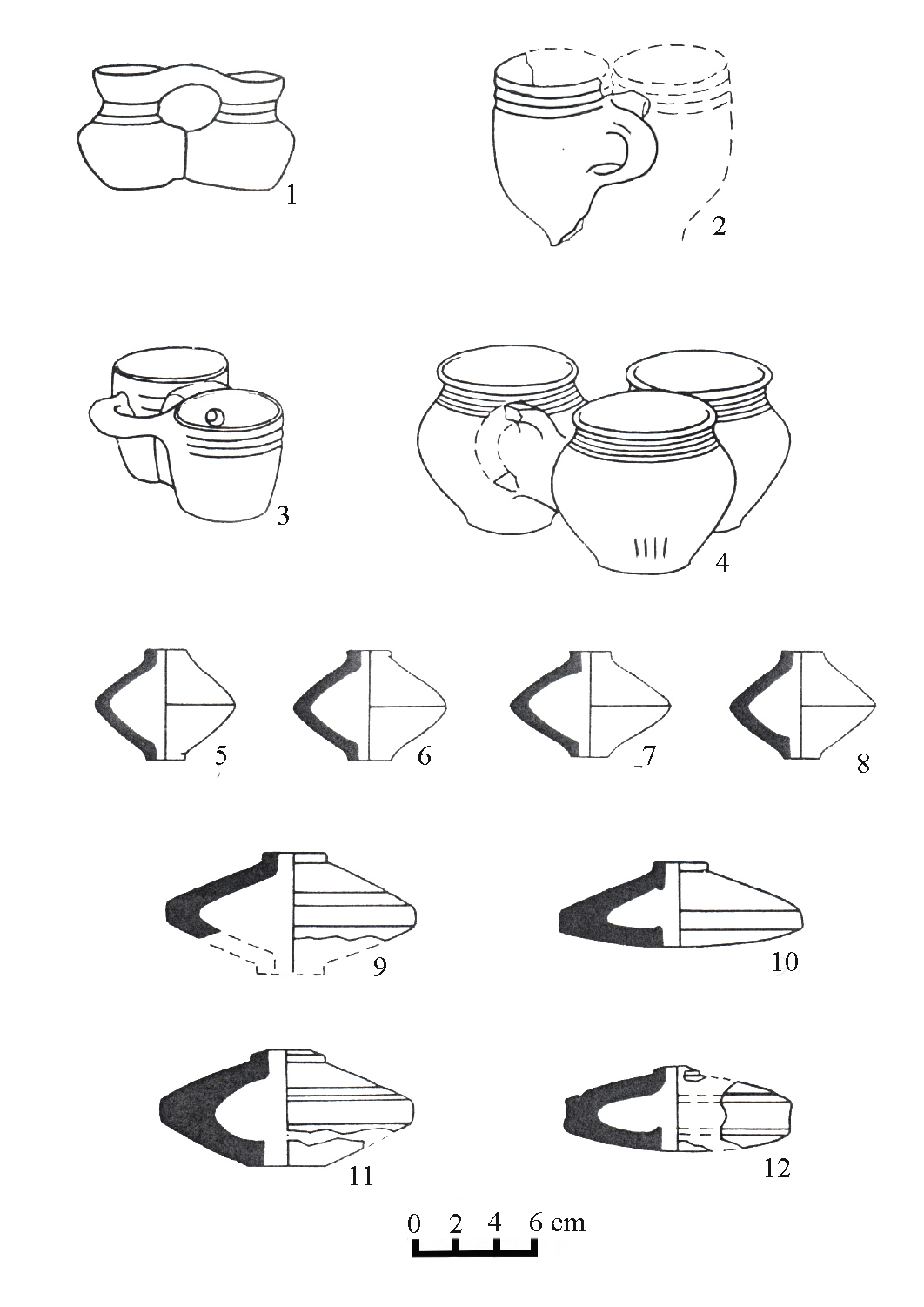

Communicating vessels

Four communicating vessels were found in Treli burial no. 16 (Figure 4: 1-4), dating from the 8th–7th centuries BC. The outer and inner surfaces of all of them are gray and smooth. Three of the four have gray structure, no. 4 is the exception with its slightly pinkish structure. The communicating vessel is a container consisting of a pair of tumblers connected by a transverse hole. One of the four vessels discussed here does not have a cross hole (no. 1). Vessel no. 2 is incomplete and therefore it is not possible to say anything about the transverse hole in this case. The handle cross-section is different for each of the four vessels: no. 4 has a rectangular cross-section, no. 3 has a round cross-section, and no. 1 and 2 have an oval cross-section.On the territory of Georgia, communicating vessels were found in Trialeti, in the Neolithic layer of Beshtasheni (Kuftin 1941: Tab.CXXIV) and in the Tsalka district (Kuftin 1948: 7-9, Tab.3). Analogues of communicating vessels have been found in the burial grounds of Koban and Upper Rutkha (Uvarova 1900: 242, pic. 97, Tab.XIII.11), and in Nesterovo burial no. 21, which dates to the Early Iron Age (Krupnov 1960: Tab.XIII1). The same vessels, approximately contemporary with the Treli specimens, are known from Saritepe (Narimanov, Khalilov 1962: 34, Fig.9), Mingechaur (Aslanov, et al. 1959: Tab.XII2), Teishebaini (Martirosyan 1964: 142, Tab.66) and Hasanlu (Ghirshman 1963: 24, Fig.2).

Figure 4. 1-4 – Communicating vessels from burial no. 16; 5-12 – Biconical vessels from burial no. 16.

Figure 4. 1-4 – Communicating vessels from burial no. 16; 5-12 – Biconical vessels from burial no. 16.

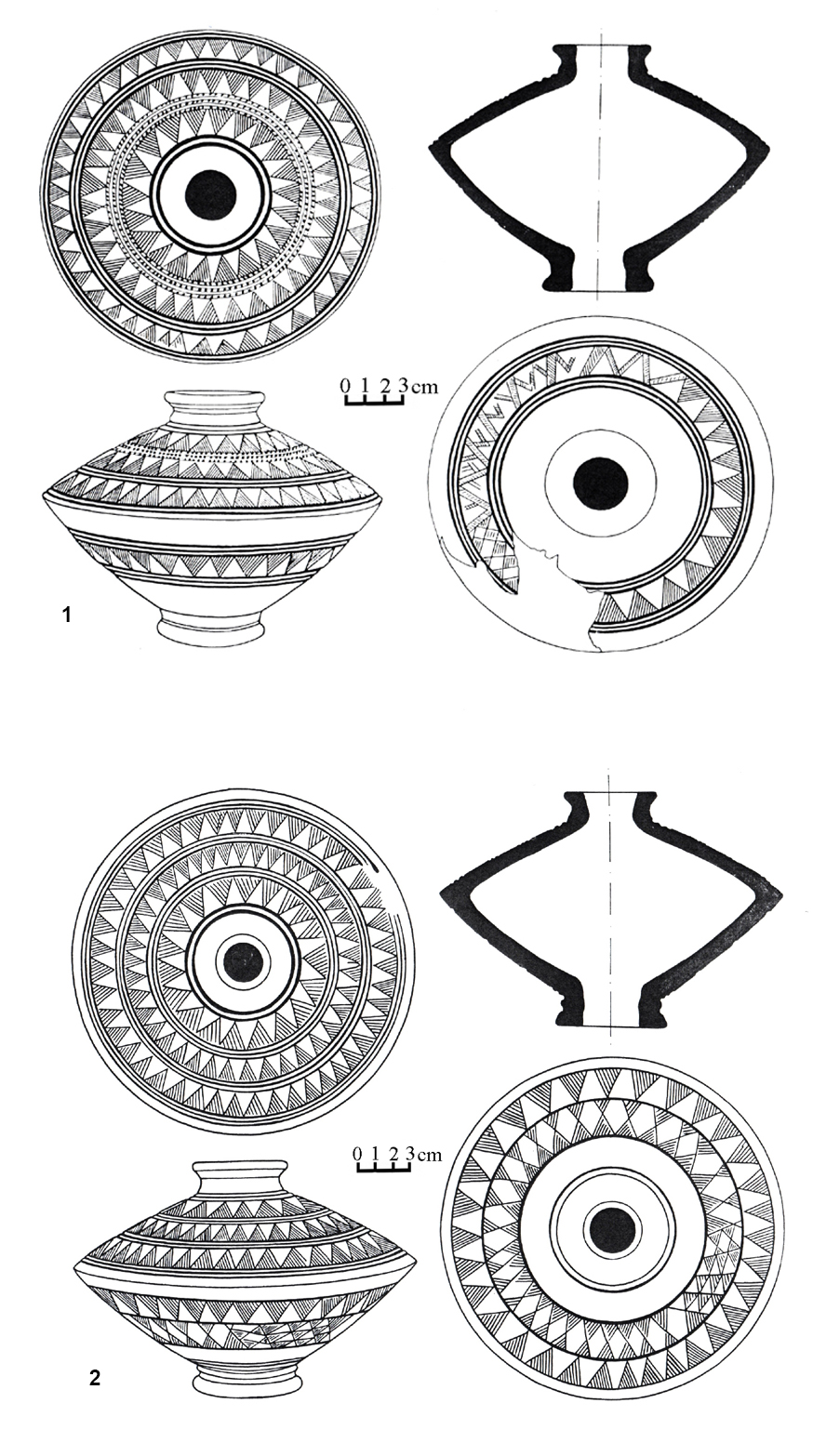

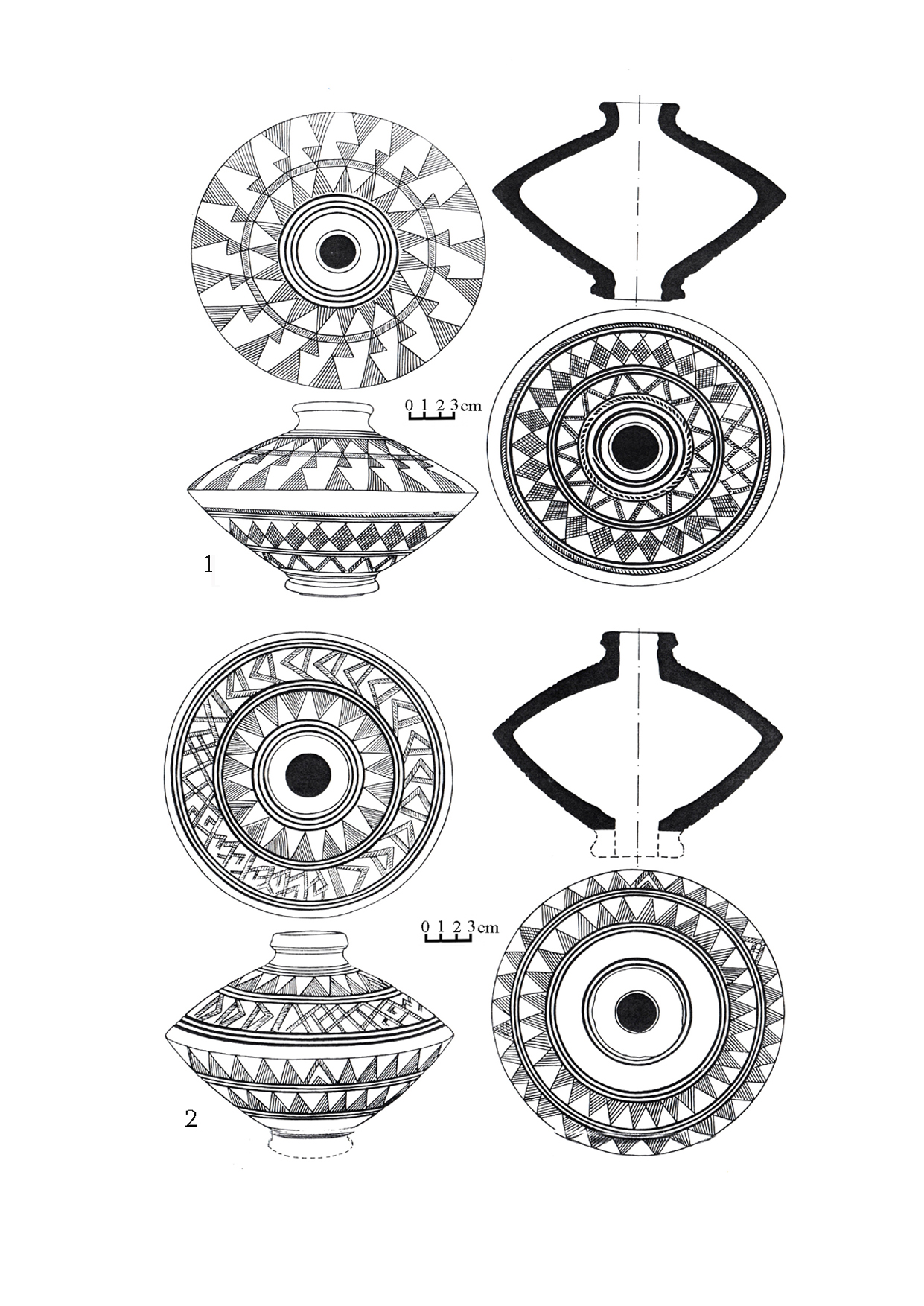

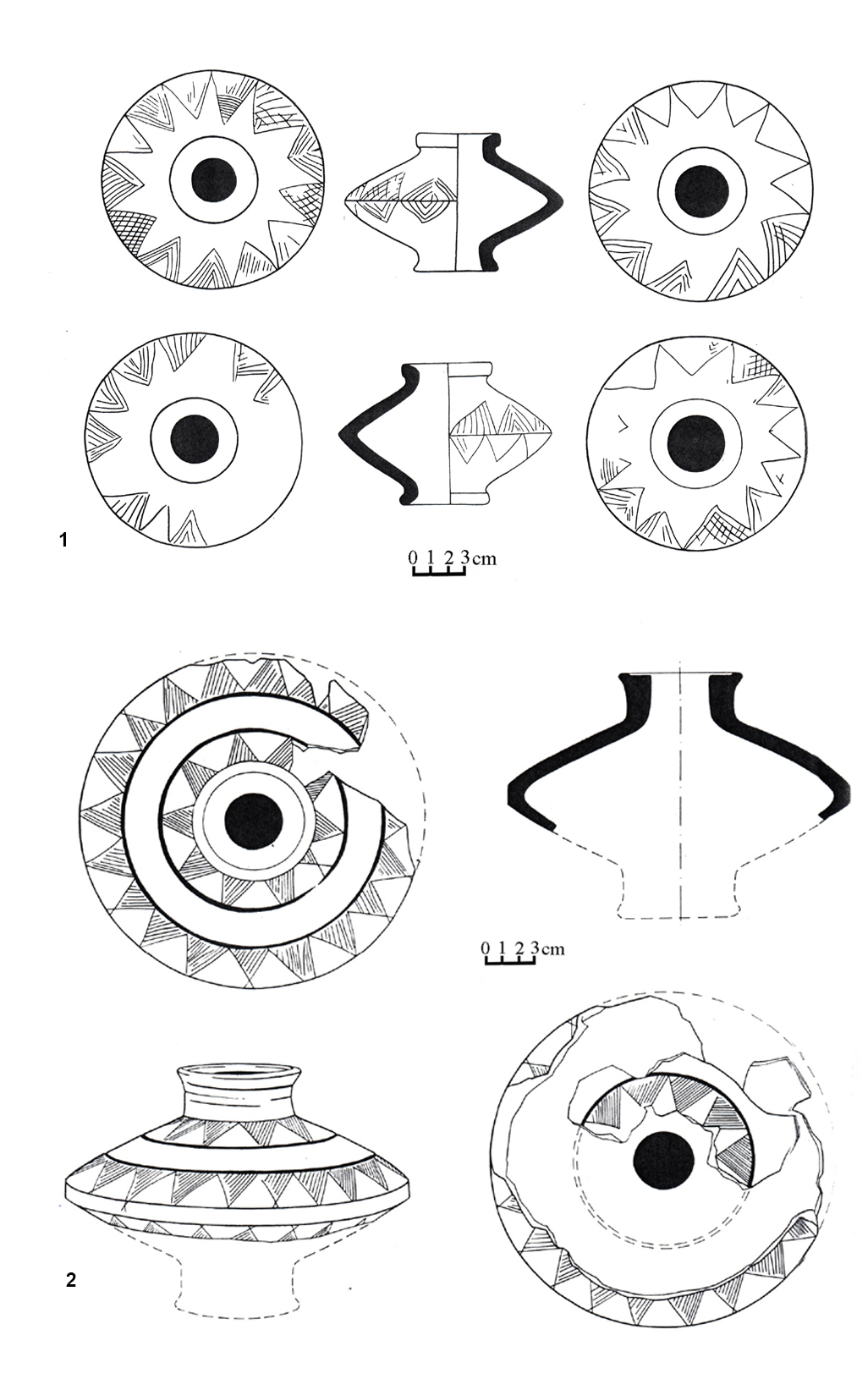

Biconical vessels

In Treli burial nos. 16 (Figure 4: 5-7; Figure) and 24 (Figure 8: 1), 18 biconical vessels of various sizes were found. They are all the same shape but in terms of size and decoration, they form two groups. Group 1 comprises plain vessels (Figure Figure 8. 1 – Biconical vessels from burial no. 24; 2 – Zoomorphic vessels from burial no. 16) and vessels with one or two concentric lines. (Figure 4: 5-8). This group, in turn, is divided into two subgroups: a) Four vessels (Figure 4: 9-12) with black, smooth outer surfaces, gray inner surfaces, and a rough pink-reddish structure. They have flat surfaces with one or two concentric lines on either side. The vessels of this subgroup are severely damaged; b) Vessels with a plain surface. All four of these (Figure 4:5-8) are the same size and have a yellowish-gray and smooth surface.The second group includes larger specimens, each of which is decorated with different geometric patterns (Figure 5-8: 1). Vessels in this group are grayish – black with well-smoothed outer surfaces, ornamented with incised and indented patterns. These geometric patterns extend over both sides of each vessel in this group. We cannot say anything about the exact purpose of these vessels, but we assume that their shape and ornamentation indicate that they were to be used as cult and ritual objects. The ornament of some of them can also be considered pictographs. No analogues of biconical vessels from Treli have been found anywhere else, which indicates their local origin.

Figure 5. 1-2 – Biconical vessels from burial no. 16

Figure 5. 1-2 – Biconical vessels from burial no. 16

Figure 6. 1-2 – Biconical vessels from burial no. 16.

Figure 6. 1-2 – Biconical vessels from burial no. 16.

Figure 7. 1-2 – Biconical vessels from burial no. 16

Figure 7. 1-2 – Biconical vessels from burial no. 16

Figure 8. 1 – Biconical vessels from burial no. 24; 2 – Zoomorphic vessels from burial no. 16

Figure 8. 1 – Biconical vessels from burial no. 24; 2 – Zoomorphic vessels from burial no. 16

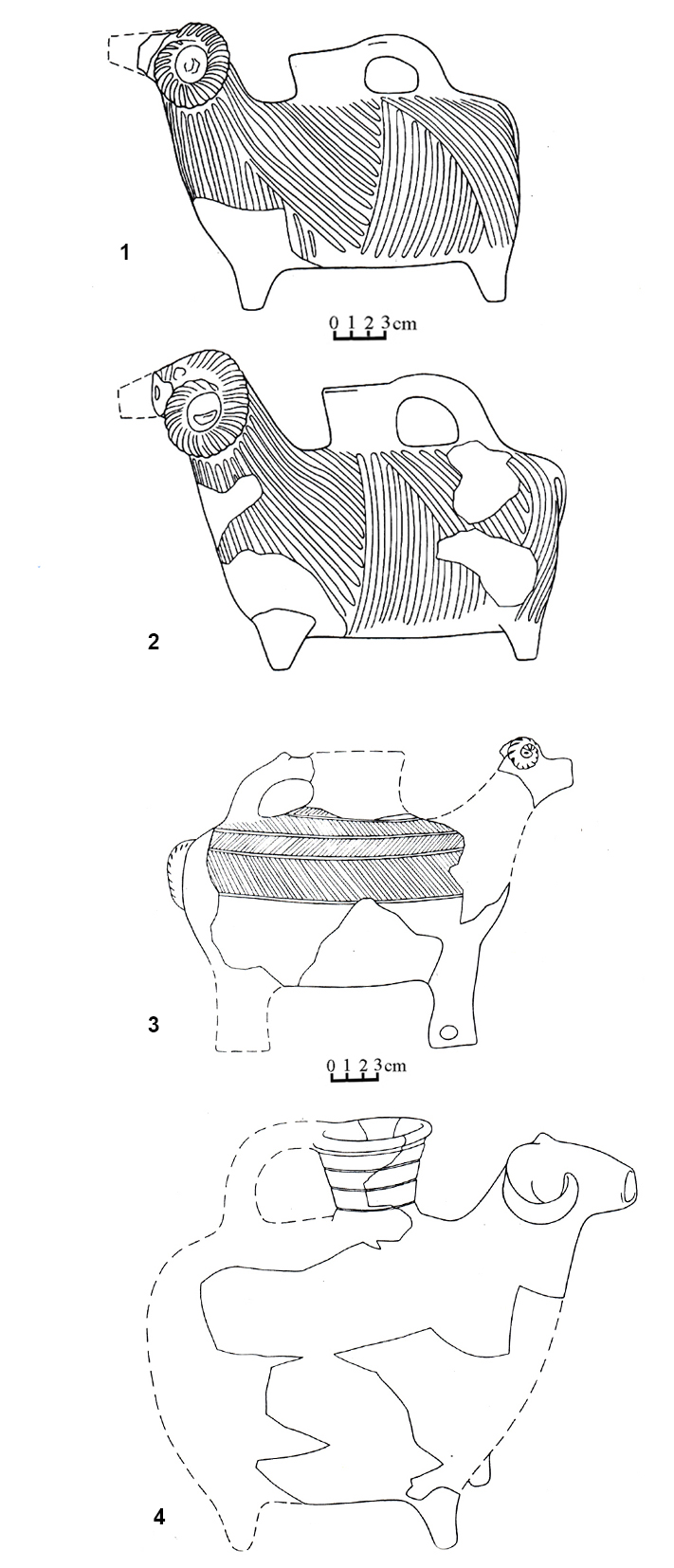

Zoomorphic vessels

In Treli burial nos.16 and 24, zoomorphic vessels in the shape of bulls, rams and birds have been found (Figure 11)4. Of the 12 vessels found in burial 16, one is an image of a bird; the rest represent rams. Four of the 12 vessels were so fragmented that it appeared not possible to restore them. The vessel in the shape of a bird is highly fragmented, which is why its shape cannot be determined. The top of this vessel resembles a bird’s head. The eyes are represented by dots, the nose (beak) with a hole is broken off. The preserved fragments of the body are covered with dotted decoration (Figure 11: 3). It has a black surface and a gray structure.Ram-shaped vessels have a nose that is elongated to a greater or lesser extent, with an opening for pouring liquid. On the animal’s back there is an opening for filling the vessel with liquid; this has a neck with a slightly outward-turned rim, that is connected to the vessel body by means of a handle with oval section. A pair among the 12 vessels have gray-blackish polished outer and inner surfaces and a structure of the same color, twisted horns and short, cut-off snouts (Figures 8 and 9).

Five vessels make up a separate group (Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11:2). These “rams” have a black, polished outer surface, gray-blackish structure and sinuous horns with transverse grooves, a long and narrow snout with a hole for pouring liquid and small clay knobs representing the eyes. Their backs are provided with slightly expanding short necks through which to fill the vessel with liquid. The bodies of the “rams” are completely decorated with carved lines, running in different directions.

Distinctive in manufacturing technique and stylized form is an unevenly annealed ram-shaped vessel with horns decorated with twisted and embossed ornament (Figure 10: 1). Its raised short tail has the same relief decoration. The oval-shaped and flattened body of the ram is stylized. It is decorated with three bands of incised lines with a herringbone pattern between them. The right front part of the ram, with a transverse hole in it, has been preserved. Presumably, the missing legs also had holes. Unlike all the other vessels, the handle of this one has a zoomorphic detail sculpted onto it. This is the so-called zoomorphic handle that is the defining feature of the monuments of Samtavro culture, but the zoomorphic vessels themselves are completely alien to the Samtavro culture. Apparently, the zoomorphic ceramics of Treli were made by a local craftsman commissioned by a foreign ethnic group that came from the south into the Digomi Valley. (for the question of cultural affiliation of Treli burial nos. 16 and 24, see: Abramishvili und Abramishvili 1995). This explains the defining feature of the local Samtavro culture – the so-called zoomorphic handle on a vessel that is alien to the local culture.

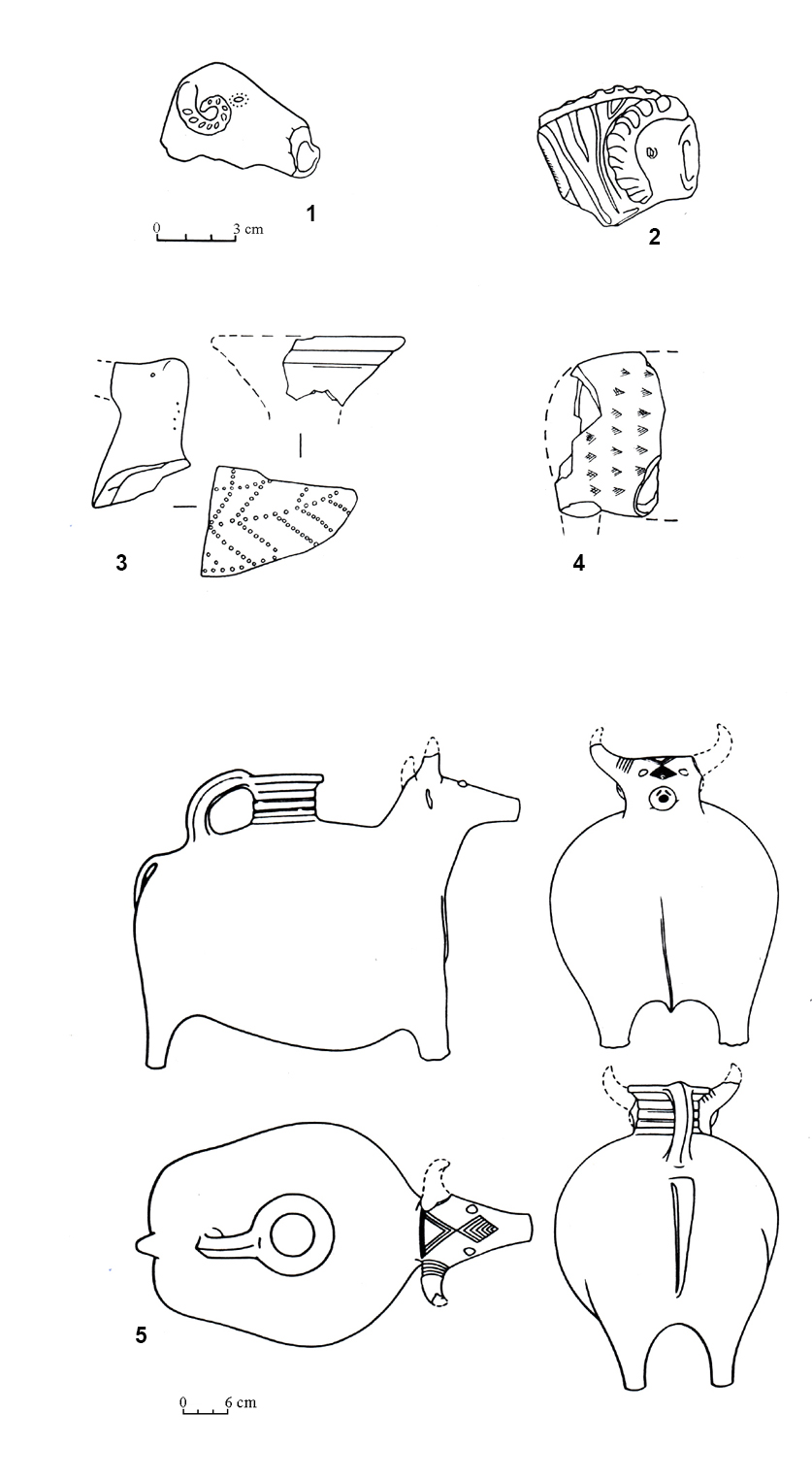

A large zoomorphic vessel depicting a bull was found at Treli burial no. 24 (Figure 11: 5). The surface of this vessel is black and polished, the structure is gray. The oblong nose has a through hole for pouring liquid. The nostrils are represented by a pair of oblique, raised lines, and the eyes are made with small knobs. Only one horn, with three circles at the bottom, has been preserved. A small ear is attached under the horn. The forehead is decorated with three downward-pointing nested triangles above a rhombus covered with a pine – tree ornament. The faceted handle of the vessel is attached to the body and to the flared rim of the opening for filling the vessel with liquid. This rim is decorated with cut lines. The “bull’s” tail is depicted in relief. A rib runs down the chest. The front part of the body is much wider than the back. The belly curves sharply at the hind legs. All these features emphasize the strength of the “bull”. Fragments of two different zoomorphic vessels were also found in the same burial, no. 24 (Figure 11: 1, 4).

On the territory of Transcaucasia, zoomorphic vessels dating from the first half of the 1st millennium BC are known from the Mingechaur 3rd mound and pit burials of the 2nd layer (Aslanov, et al. 1959: Fig.XXXVII, XLII), Musi-Yeri (Morgan 1889: 155, Tab.169), and Verishen (Avetisyan, Bobokhyan 2012: Tab.VII.5). Zoomorphic vessels dating from the first half of the first millennium BC have also been found in Iran; in the Amlash cemetery – 10th and 9th-8th centuries BC (Porada 1963: 92; Ghirshman 1963: 32, 35, 38, fig.34, 47), in Marlik – 10th century BC (Negahban 1962: pic.9, 11), in Khurvin 8th-7th centuries BC (Vanden Berghe 1964: Tab. XXXII, fig.221, 222; Ghirshman 1963: 19, fig.17), in Talish (Morgan 1925: 280, 281, fig. 267-279), in Kalardash 8th-7th centuries BC (Ghirshman 1963: 97, fig.128), in Makuda and Suza (Ghirshman 1963: 287, 289, fig.345, 347), in Zivie – 7th century BC (Ghirshman 1963: 322, fig.394), etc. Zoomorphic vessels have been found in the North Caucasus, namely at the Upper Rutkha (Uvarova 213, fig.184) and Faskau cemeteries (Ibid, Fig.XI.1), and at Kumbulta burial no. 4 (Ibid: 213, fig.184). Most like the zoomorphic vessels from the Treli cemetery is a vessel of the 8th–7th centuries BC, found in Luristan, at the Var-Kabud burial ground (Vanden Berghe 1968:61), which is very close to the vessel found in burial no. 24 (Figure 11: 5). The Treli cemetery zoomorphic vessels were produced locally and belong to the period of wide development of iron. The basis for such a conclusion has been provided by a black polished outer surface, grayish structure and zoomorphic handle (Figure 10: 4) so characteristic of Georgian pottery.

Figure 9. 1-3 – Zoomorphic vessels from burial no. 16.

Figure 9. 1-3 – Zoomorphic vessels from burial no. 16.

Figure 10. Zoomorphic vessels from burial no. 16.

Figure 10. Zoomorphic vessels from burial no. 16.

Figure 11. 1-5 – Zoomorphic vessels from burial no. 24.

Figure 11. 1-5 – Zoomorphic vessels from burial no. 24.

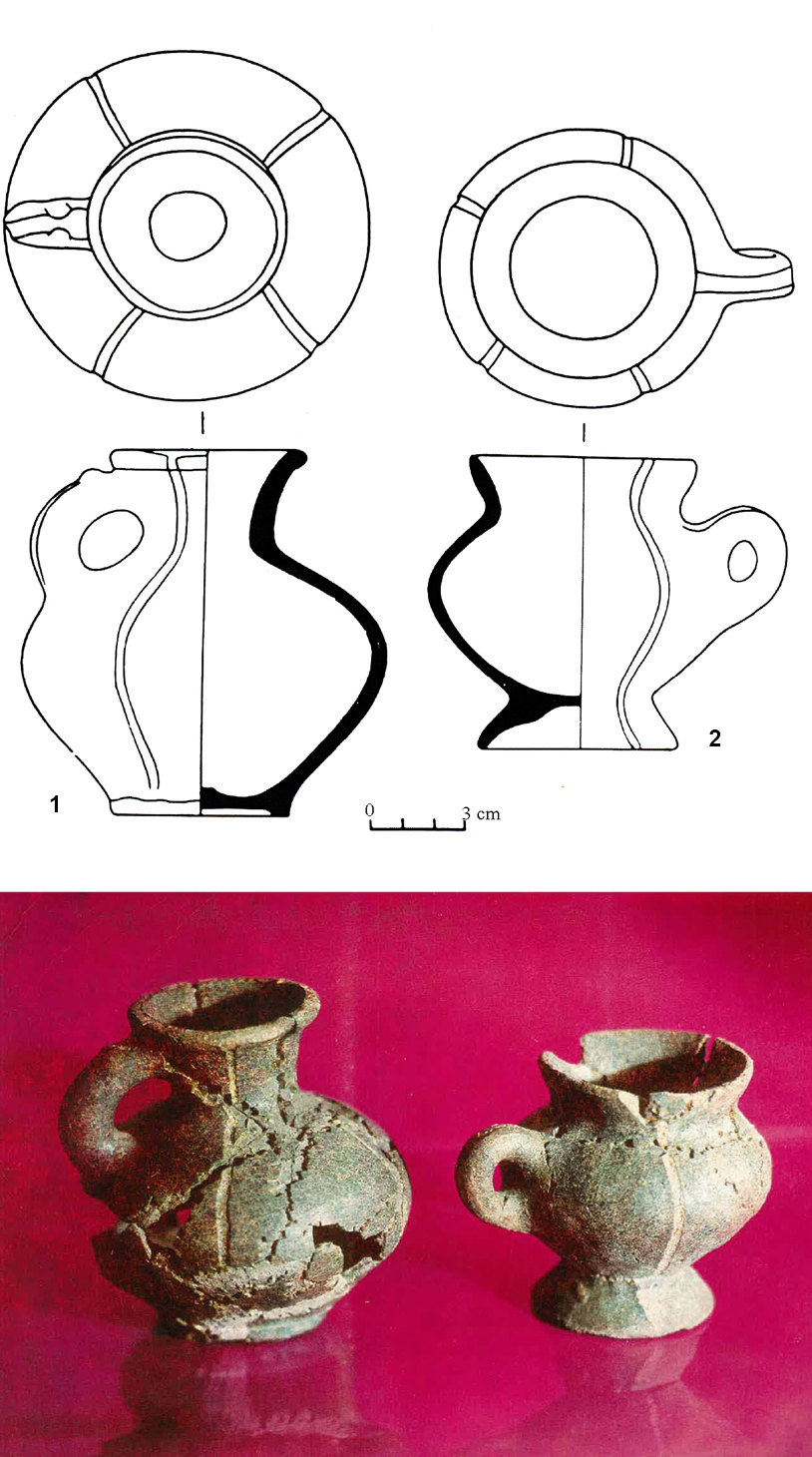

Glazed pottery

Two examples of glazed pottery come from Treli burial no. 16, dated to the 8th–7th centuries BC (Figure 12). One of them is a single-handled hollow-based “drinking” vessel (Figure 12: 2) and the other is a small pitcher (Figure 12:1). Their outer surfaces are greenish and their structure buff – grayish. Each of them is decorated with five lengthwise lines.Speaking about the origins of Southern Caucasian glazed vessels, scholars propose entirely different conclusions. Some of them consider that the glazed pottery was produced locally (Morgan 1896: 105; 1941: 52-53; Baramidze 1965: 38), while others insist that it was imported from the Near East (Kushnaryova 1959: 383-385; Pasek, Latynin1926: 63; Aslanov, et al. 1959: 98,112,113; Mamaiashvili 1970: 11; Pitskhelauri 1973: 103).

The earliest artefact with glaze in Georgia is a bead from Trialeti kurgan no. 15, dated to the Middle Bronze Age (Zhorzhikashvili, Gogadze 1974: 90). Late Bronze-Early Iron Age glazed pottery was found in Samtavro cemetery burial nos. 77, 96b, 119, 168, 208, 216, 289, and 591, in Maralin-Deresi (Santa) burial no. 12 (Kuftin 1941: 1941: fig.XX); at Meli-Ghele 2nd sanctuary (Pitskhelauri 1973: 1973: 101); and in Treli burial no. 16.

In Azerbaijan, glazed vessels were found in the Mingechaur mound nos.2 and 4 (Aslanov et al. 1959: 112) and in Talish, John cemetery (Kushnaryova 1959: 383-385). In Armenia, glazed ceramics of the same period were found on Karmir-Blur (Piotrovsky 1955: 21), and Oshakan (Yesayan, Kalantaryan 1988: colored pl.2)5).

The earliest examples of glazed pottery in South Caucasia come from Samtavro burial nos.77 and 96b, dating from the second half of the 12th century BC (Abramishvili 1961: 328-330). Chronologically, they are followed by Samtavro burial nos. 208 and 591, dated in general to the 11th century BC (Ibid: 330), then Samtavro burial nos. 119, 168, and 289, which date from the second half of the 10th century and the 9th century BC (Ibid: 334). The latest burial is no. 216, which dates to the 8th–7th centuries BC. Among other things, a hollow-based drinking vessel, glazed vessel of the same shape, an iron knife, 2 bronze pins, carnelian and glass beads, etc. were found in this burial. Material of this kind generally belongs to the 8th–6th centuries BC, but taking into account the fact that burial no. 212, which contain iron akinakes and dates from the second half of the 7th century and the 6th century BC, stratigraphically lies above burial no. 216 (Abramishvili 1957: fig.II), the latter belongs to the previous chronological group (8th century-the first half of the 7th century BC). Glazed pottery from Maralin-Deresi (Santa), Treli and Mingechaur cemeteries must be contemporaneous. Ceramics found in Armenia, according to available materials, should also belong to the era of wide development of iron. Based on the assumptions just made, glazed ceramics on the territory of the South Caucasus originate from the second half of the 12th century and continue until the 6th century BC.

Glazed ceramics found in Georgia are mostly of the same shape – one-handled drinking” vessels with hollow heels. Such forms are typical for Georgia. There is also a small jug (Treli burial no. 16) and a narrow-waisted drinking vessel (Samtavro burial no. 77). In Armenia and Azerbaijan, glazed ceramics are mainly represented by bowls. Some of them are tripods, others have handles (Oshakan). There are also cups (Mingechaur 4th mound) and a pot with three handles (Mingechaur mound no. 2).

In the Treli cemetery, unglazed pottery with hollow heel is found in burials from the 13th to the 7th centuries BC (Abramishvili et al. 1978: 138-139). This group of artefacts includes the glazed pottery from Treli burial no. 16 (Figure 12: 2). The ceramic vessel with hollow heel is a “drinking” vessel baked in a yellowish-grayish color and has a smoothed outer surface. It has a short or somewhat raised neck, a body narrowing from the shoulder to the bottom, a hollow base on a raised heel, and a single handle. In 15 burials of the 11th–6th centuries BC, 26 vessels with a hollow base were found in the Treli cemetery (burial nos.16 (4 units), 28 (2 units), 30, 49 (2 units), 73, 79, 113, 119, 121, 123 (3 units), 124 (2 units), 133, 134, 137 (2 units), 144, 247 (2 units). Most of these are decorated with geometric patterns, but there are also quite plain specimens (burial nos. 137, 247). In several cases, a piece of obsidian was inserted into the bottom (burials nos. 16, 123). No other types of obsidian vessels were found at the contemporaneous monuments (Abramishvili 1978:138). Ceramics with a hollow base were found on the monuments of the Late Bronze–Early Iron Age of the Samtavro cemetery and the Doghlauri settlement (Ghambashidze 1974: 155, Fig.I,3). They were found in large numbers at the Narekvavi cemetery of the same period (Apakidze 2000: Tab.XIII595,596, XXI672, XX678, XXVII701,702; Apakidze 1999: Tab.XXIII410, XXXIV450; Nikolaishvili, Gavasheli 2007: Tab.XIII920,921,922; XV,945,950; XXI999; XXXIII1105; XXXIV1122; LVI1328, LXXVI1502, LXXXVI15377).

Transcaucasian glazed ceramics are greenish turquoise, often with yellow lines intersecting in some cases with brownish ones. The structure is mostly grayish (two items each from Samtavro burial no. 77 and Treli burial no. 16) or grayish black (Samtavro burial nos. 96b, 119, 208, 289 and Maralin-Deresi burial no. 2). In Armenia and Azerbaijan, the structure of glazed ceramics is mostly white (Oshakan jug and vessel from Mingechaur mound no. 4). Fragments of glazed ceramics from Meli-Ghele 2 and glazed beads from Treli burial no. 96 and Samtavro burials also have a white structure.

We consider it indisputable that the art of glazing came to Transcaucasia from the Near East. Presumably, glazed ceramics made from white clay are also Near Eastern imports. It is important to note that the glazed white clay beads originating from Treli burial no. 96 and dating from the 13th century BC chronologically precede the glazed ceramics found in Transcaucasia. We consider that all the glazed vessels found in Georgia were locally produced, with the exception of the Meli-Ghele 2 ceramics made from white clay. This is indicated by the fact that similar but unglazed clay vessels chronologically precede glazed ones; for example, vessels with a narrow waist are typical for monuments dating from the 14th century BC (Samtavro no. 153, Karsani nos. 64–67 and Treli no. 90 burials). In addition, among glazed ceramics, the most common form is vessels with a hollow heel. Similar but unglazed pottery is found in burials of an earlier period, dating from the 13th century and the first half of the 12th century BC (Abramishvili 1978:138-139). The specified forms are typical for Inner and Lower Kartli and are found in the cemeteries of Samtavro (burial nos. 1, 41, 44, 51, 89, 91, 137, 186, 211, 222, 225, 236, 276, 281), Treli (burial nos. 11, 12, 23, 28, 38, 39, 41, 45, 49, 73, 79, 100, 102, 119, 121, 123), Kaspi (Baramidze 1965:38), Plavismani (Makalatia 1930: 233), Dvani (Makalatia 1948: 36), Nuli, and Dmanisi (Nioradze 1947: 52, 53, fig.36), as well as on the settlement of Doghlauri (Gambashidze 1974:137, Tab.I, 4-5), etc. Such glazed or unglazed forms are not found not only in the Near East, but also outside of Georgia, even in Transcaucasia (Abramishvili 1978:139). There are only two exceptions: one comes from the Redkin Lager (Martirosyan 1964:fig.78.14), and the other from Leninakan – a black – polished sample with a hollow heel (it is kept in the Yerevan Museum). The fact that the glazed vessels found in Georgia have a gray structure is also proof of local production. Such a structure is generally characteristic of the clay vessels of the South Caucasus in the period in which we are interested. During the same period, well-dissected clay vessels with a red structure were found in the Near East. Based on all of the above, we have no reason to consider the glazed vessels found in Georgia, with the exception of Meli-Ghele, to be non-native.

Figure 12. Glazed vessels from burial no. 16 .

Figure 12. Glazed vessels from burial no. 16 .

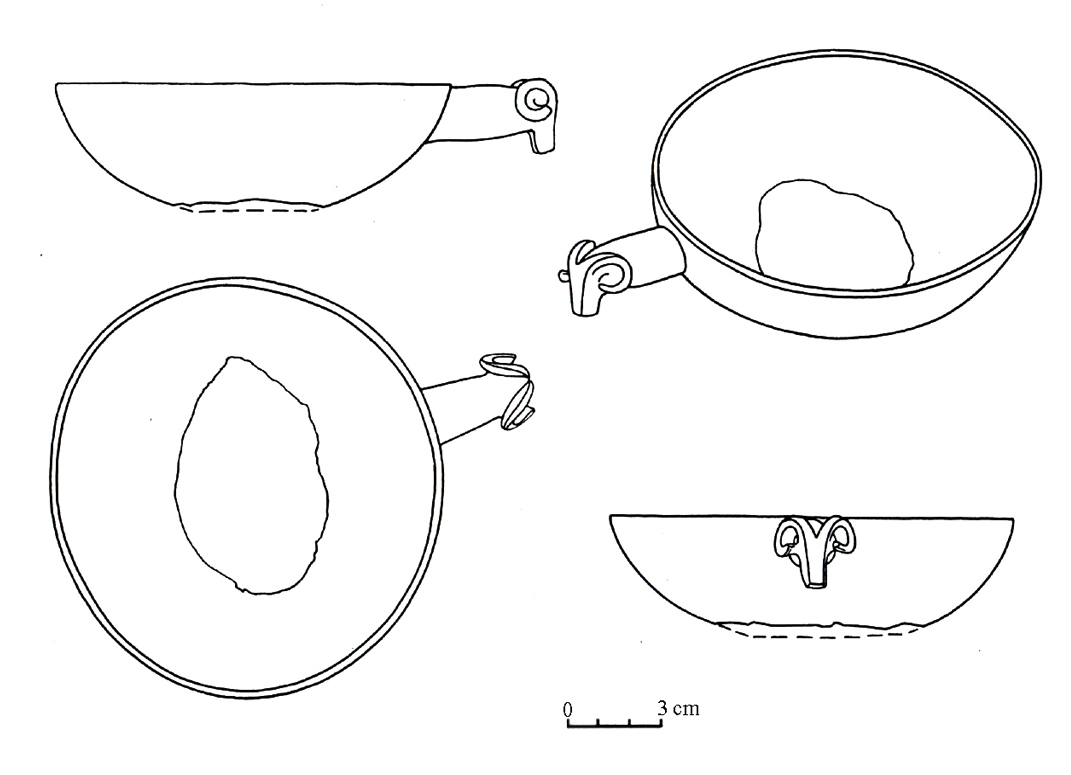

აგალმატოლიტის ფიალა

A stone (agalmatolite) bowl of crimson colour was found in burial no. 24 of the Treli burial ground. Its handle ends with the image of a ram’s head (Figure 13). The bottom of the vessel is damaged, but according to Azerbaijan and Iranian analogues, the Treli item should have had a base raised on the heel. Bowls with handles ending with images of a ram’s head are found in northwestern Iran: Suza (Porada 1963: Tab.91), Tepe Sialk A and B necropolis (Ghirshman 1939: Tab.I2,3), Tepe Giyan cemetery 1 (Shaeffer 1948: Figs.242, 246), in the vicinity of Sawah (Vanden Berghe 1959: 125), and in the Hasanlu cemetery (Vanden Berghe 1959: fig.139); and in Eastern Transcaucasia: Mingechaur (Aslanov et al. 1959: 96-98, 151, fig.XLVI, 14), Khojaly (Kushnaryova 1959: fig.3), Khanlar (Narimanov 1960: 713), the village of Kasum-Ismailovo (Narimanov 1960:711,714, fig.1 ), Khachbulag (Kesamanly 1966: fig.2).Monuments of Azerbaijan containing agalmatolite bowls with handles with the image of a ram’s head date back to the 8th–7th centuries BC (Abramishvili 1995:32-33). Transcaucasian bowls, like the Treli bowl, are made of crimson stone. Some of them are encrusted with white mass (Mingechaur, Khojaly). Unlike Transcaucasian vessels, the Iranian samples are made of bitumen and clay. The Treli bowl is much closer to Azerbaijani samples than to its Iranian counterparts, and it must have originated in Azerbaijan.

სურათი 13. Figure 13. Agalmatolite bowl from burial no.16.

სურათი 13. Figure 13. Agalmatolite bowl from burial no.16.

Notes:

1. Treli necropolis is located between Mtskheta and Tbilisi, at the foot of the eastern slope of the natural hills of the Dighomi Valley, located along the so-called Georgian Military Road.

2.The finds from the Treli cemetery, dated to the 13th–12th centuries BC, were published by R. Abramishvili (Abramishvili 1978). The tables illustrating the material from the subsequent period, including those presented in this article, were likewise prepared on the basis of Rostom Abramishvili’s drawings.

3. In general, on the territory of Georgia, the archaeological culture containing ceramics with zoomorphic handles is not genetically related to its predecessor, the local archaeological culture, as already noted by Boris Kuftin, the first researcher of the monuments of this period (Kuftin 1950: 152). This point of view is shared by other researchers (see: Mikeladze 1974). From the point of view of Rostom Abramishvili, northeastern Anatolia presumably must have been the area from which ceramics with zoomorphic handles came (Abramishvili 1981). Here, it should be recalled that pottery with zoomorphic handles was found in the fifth layer of Beicesultan, which is dated from 1900 to 1750 BC (Lloyd, Mellaart 1956: 125, Fig.3). If we follow Rostom Abramishvili’s opinion, this region is not the main area of distribution of vessels with zoomorphic handles. They must have spread here too from northeastern Anatolia.

On the basis of ceramics with sculpted details on their handles, the archaeological area of the society carrying ceramics with zoomorphic handles was identified, in which Colchian archaeological culture (western Georgia) and the Samtavro archeological culture (part of eastern Georgia) are united on the territory of Georgia (Abramishvili 1995: 193).

4. The description of zoomorphic vessels is given by R. Abramishvili et Al. Ramishvili (Abramishvili, Ramishvili 1971).

5. According to the archival data of Rostom Abramishvili, glazed vessels were also found in Kirovakan, Aigevan, Dvin on the territory of Armenia.

Refereces:

Abramishvili, R. 1957. “Samtavros samarovanze aghmochenili gvianbrinjaosa da rkinis khanis dzeglebis datarighebistvis” (Towards the dating of the Late Bronze–Early Iron Age sites at the Samtavro cemetery). Moambe, the Journal of the Georgian State Museum, XIXA–XXIB: 115–139 (in Georgian).

Abramishvili, R. 1961. “Rkinis atvisebis sakitkhistvis agmosavlet saqartvelos teritoriaze” (For the development of iron in the territory of eastern Georgia). Moambe, the Journal of the Georgian National Museum, XXII-B: 291–380 (in Georgian).

Abramishvili, R.; Ramishvili, Al. 1971. “1971 tsels trelis samarovanze chatarebuli arqeologiuri kvleva-dziebis angarishi” (Report of archaeological research in 1971 on the Treli burial ground). Unpublished manuscript (in Georgian).

Abramishvili, R. (ed.). 1978. Tbilisis arqeologiuri dzeglebi (Archaeological sites of Tbilisi), Vol. I. Tbilisi: Metsniereba (in Georgian).

Abramishvili, R.; Giguashvili, N.; Kakhiani, K. 1980. Ghrmakhevistavis arqeologiuri dzeglebi (Archaeological sites of Ghrmakhevistavi). Tbilisi: Metsniereba (in Georgian).

Abramishvili, R. 1981. “Amierkavkasiis arqeologiuri kulturebi gvianbrinjao-adrerkinis khanashi” (Archaeological cultures of Transcaucasia in the Late Bronze–Early Iron Age). Conference paper, unpublished (in Georgian).

Abramishvili, R. 1995. “Neue Angaben über die Existenz des thrako-kimmerischen Elements und des sog. skythischen Reiches im Osten Transkaukasiens.” Archäologischer Anzeiger, 1: 23–39.

Abramishvili, R.; Abramishvili, M. 1995. “Archäologische Denkmäler in Tbilisi unterwegs zum Goldenen Vlies.” In A. Minor & W. Orthmann (eds.), Archäologische Funde aus Georgien, 187–205. Saarbrücken.

Akhvlediani, N.; Sultanishvili, Ir. 2010. “Brinjaos potliseburi satevrebi” (Leaf-like bronze daggers). Dziebani saqartvelos arqeologiashi, 19: 126–139 (in Georgian).

Apakidze, A. (ed.). 1999. Mtskheta 1998, Narekvavi I. Tbilisi: Metsniereba (in Georgian).

Apakidze, A. (ed.). 2000. Mtskheta 1999, Narekvavi II. Tbilisi: Metsniereba (in Georgian).

Aslanov, G. M.; Vaidov, R. M.; Jone, G. I. 1959. Drevnii Mingechaur (Old Mingechaur). Baku: Academy of Sciences of the Azerbaijan SSR (in Russian).

Avalishvili, G. 1974. Kvemo Kartli dzv.ts. I atastsleulis I nakhevarshi (Kvemo Kartli in the first half of the 1st millennium BC). Tbilisi: Tbilisi State University Press (in Georgian).

Avetisyan, P.; Bobokhyan, A. 2012. “The pottery traditions in Armenia from the eighth to the seventh centuries BC.” In S. Kroll et al. (eds.), Biainili-Urartu, 373–378.

Baramidze, M. 1965. “Kaspis samarovani” (Kaspi necropolis). Masalebi saqartvelos da kavkasiis arqeologiisatvis, IV: 31–66 (in Georgian).

Chubinashvili, T. 1957. Mtskhetis udzvelesi arqeologiuri dzeglebi (Ancient archaeological sites of Mtskheta). Tbilisi: Teqnika da Shroma (in Georgian).

Ghambashidze, O. 1974. “Gvianbrinjaos khanis dzeglebi sopel Doghlauridan” (Late Bronze Age sites from Doghlauri). Masalebi saqartvelos da kavkasiis arqeologiisatvis, VI: 150–167 (in Georgian).

Ghambashidze, O.; Kvizhinadze, K. 1982. “Raboty Meskhet-Dzhavakhetskoi arkheologicheskoi ekspeditsii v 1976–1979 gg.” In A. Kalandadze (ed.), Arkheologicheskie issledovaniya na novostroikakh Gruzinskoi SSR, 47–53 (in Russian).

Ghirshman, R. 1939. Fouilles de Sialk, près de Kashan, Vol. II. Paris: Paul Geuthner.

Ghirshman, R. 1963. Perse, Proto-Iraniens, Mèdes, Achéménides. Paris.

Kesamanly, G. 1966. “Pogrebenie s bronzovym poyasom iz Khachbulaga” (Burial with bronze belt from Khachbulag). Sovetskaya Arkheologiya, 3: 221–226 (in Russian).

Koridze, D. 1955. Tbilisis arqeologiuri dzeglebi (Archaeological monuments of Tbilisi), Vol. I. Tbilisi (in Georgian).

Kuftin, B. 1941. Arkheologicheskie raskopki v Trialeti. Tbilisi (in Russian).

Kuftin, B. 1948. Arkheologicheskie raskopki v Tsalkinskom raione v 1947 g. Tbilisi (in Russian).

Kuftin, B. 1949. Arkheologicheskaya marshrutnaya ekspeditsiya 1945 goda v Yugo-Osetiyu i Imeretiyu. Tbilisi (in Russian).

Kuftin, B. 1950. Materialy k arkheologii Kolkhidy, Vol. II. Tbilisi (in Russian).

Kushnaryova, K. 1959. “Arkheologicheskie raboty 1954 g. v okrestnostyakh s. Khojaly.” MIA SSSR, 67: 370–387 (in Russian).

Krupnov, E. 1960. Drevnyaya istoriya severnogo Kavkaza. Moscow (in Russian).

Lloyd, S.; Mellaart, J. 1956. “Beycesultan Excavations, Second Preliminary Report.” Anatolian Studies, 6: 101–135.

Mamaiashvili, N. 1976. Paiansi shuasaukuneta saqartveloshi (Faience in medieval Georgia). Tbilisi: Metsniereba (in Georgian).

Makalatia, S. 1930. “Plavismanis udzvelesi nekropoli.” Moambe, V: 223–228 (in Georgian).

Makalatia, S. 1948. Dvanis nekropolis arqeologiuri gatkhrebi. Tbilisi (in Georgian).

Martirosyan, A. 1954. Raskopki v Golovino. Yerevan (in Russian).

Martirosyan, A. 1964. Armeniya v epokhu bronzy i rannego zheleza. Yerevan (in Russian).

Mikeladze, T. 1974. Dziebani Kolkhetisa da samkhret-aghmosavlet Shavizghvispiretis mosakhleobis istoriidan. Tbilisi: Metsniereba (in Georgian).

Muskhelishvili, D. 1978. Khovles namosakhlaris arqeologiuri masala. Tbilisi: Metsniereba (in Georgian).

Morgan, J. 1889. Mission scientifique au Caucase, Vol. I. Paris.

Morgan, J. 1896. Mission scientifique en Perse, Vol. IV/1. Paris.

Morgan, J. 1925. La Préhistoire orientale. Paris.

Narimanov, I. 1960. “Razrushennyi kurgan sela Kasum-Ismailova.” Doklady AN AzSSR, 7: 711–714 (in Russian).

Narimanov, I.; Khalilov, J. 1962. “Arkheologicheskie raskopki na kholme Sary-Tepe.” Material’naya kul’tura Azerbaidzhana, IV: 6–67 (in Russian).

Negahban, E. 1962. “Further Finds from Marlik.” The Illustrated London News, May 5.

Nioradze, G. 1947. “Dmanisis nekropoli da misi zogierti tavisebureba.” Moambe, XIV-B: 1–66 (in Georgian).

Nikolaishvili, V.; Gavasheli, E. 2007. Narekvavis arqeologiuri dzeglebi. Tbilisi (in Georgian).

Pasek, T.; Latynin, B. 1926. “Khodzhalinskii kurgan.” Izvestiya obshchestva izucheniya Azerbaidzhana, 2: 58–66 (in Russian).

Piotrovsky, B. 1955. Karmir-Blur, Vol. III. Yerevan (in Russian).

Pitskhhelauri, K. 1973. Aghmosavlet saqartvelos tomta istoriis dziritadi problemebi. Tbilisi: Metsniereba (in Georgian).

Porada, E. 1963. L’Iran ancien: l’art à l’époque préislamique. Paris.

Schaeffer, Cl. 1948. Stratigraphie comparée et chronologie de l’Asie occidentale. Oxford.

Tushishvili, N. 1972. Madnistchalis samarovani. Tbilisi: Metsniereba (in Georgian).

Uvarova, P. 1900. “Mogilniki severnogo Kavkaza.” Materialy po arkheologii Kavkaza, VIII (in Russian).

Vanden Berghe, L. 1959. Archéologie de l’Iran ancien. Leiden.

Vanden Berghe, L. 1964. La nécropole de Khurvin. Istanbul.

Vanden Berghe, L. 1968. À la découverte des civilisations de l’Iran ancien. Brussels.

Yesayan, S.; Kalantaryan, A. 1988. Oshakan, Vol. I. Yerevan (in Russian).

Zhorzhikashvili, L.; Gogadze, E. 1974. Pamyatniki Trialeti epokhi rannei i srednei bronzy. Tbilisi (in Russian).