ხარაგაულის მღვიმე, 2023 წელს ჩატარებული არქეოლოგიური სამუშაოს ანგარიში

თენგიზ მეშველიანი, ნინო ჯაყელი, მარეიკე შტალშმიდტი, თომას ბერდი, ერელა ჰოვერსიMoambe, Bulletine of the Georgian National Museum, XI (57-B): 1-9, 2024

Accepted: დეკემბერი, 2024 წელი

Published: დეკემბერი, 2025 წელი

Keywords: მღვიმე, პალეოლითი, დასავლეთ საქართველო

აბსტრაქტი

ხარაგაულის მღვიმე 2018 წელს შემთხვევით აღმოჩნდა ხარაგაულის მუნიციპალიტეტში არქეოლოგიური დაზვერვების ჩატარების დროს. იგი გამოჩნდა მას შემდეგ, რაც 2014 წელს ხარაგაულთან, სოფელ ბაზალეთის ტერიტორიაზე ე.წ. მე-12 გვირაბთან მოხდა კლდის მასივის აფეთქება. დაზვერვების შედეგად, წინასწარულმა სამუშაოებმა დაგვანახა, რომ საქმე გვაქვს შუა პალეოლითის ადამიანის სადგომთან. მღვიმის ჭრილში გამოჩნდა ორი კულტურული ფენა, რომელთა შორის ქვედა ფენის მასალა ტიპოლოგიურად ძალიან არქაულად ჩანდა. ამ აღმოჩენამ დიდი ინტერესი გამოიწვია და ჩვენ შემოგვიერთდნენ ჩვენი უცხოელი კოლეგები, პროფ. ერელა ჰოვერსი (იერუსალიმის უნივერსიტეტი). პროფ. მარეიკ შტალშმიდტი, თომას ბერდი (ვენის უნივერსიტეტი), და ჩვენი კოლეგები საქართველოს ეროვნული მუზეუმიდან დოქტ. ნინო ჯაყელი, დოქტ. ელისო ყვავაძე და დოქტორანტი ნიკოლოზ ვანიშვილი. ეს ყველაფერი იმდენად საინტერესო აღმოჩნდა, რომ პირველივე მოთხოვნით მოვიპოვეთ ნაციონალური გეოგრაფიის საზოგადოების (NGF) ფინანსური გრანტი, თუმცა კოვიდის პანდემიის გამო 2019-22 წლებში ვერ მოვახერხეთ ფართომასშტაბიანი სამუშაოების ჩატარება. მხოლოდ 2023 წელს შევძელით შედარებით სრულფასოვანი სამუშაოების ჩატარება. გაიწმინდა და პრეპარაცია გაუკეთდა მეტრ-ნახევარი სიგანის ნიადაგს. მთელი ჭრილის სიღრმეზე, აღებულ იქნა ნიმუშები აბსოლუტური თარიღებისთვის, დნმ-ს დადგენისთვის, პალინოლოგიური ნიმუშებისთვის და სხვა ანალიზებისათვის.

***

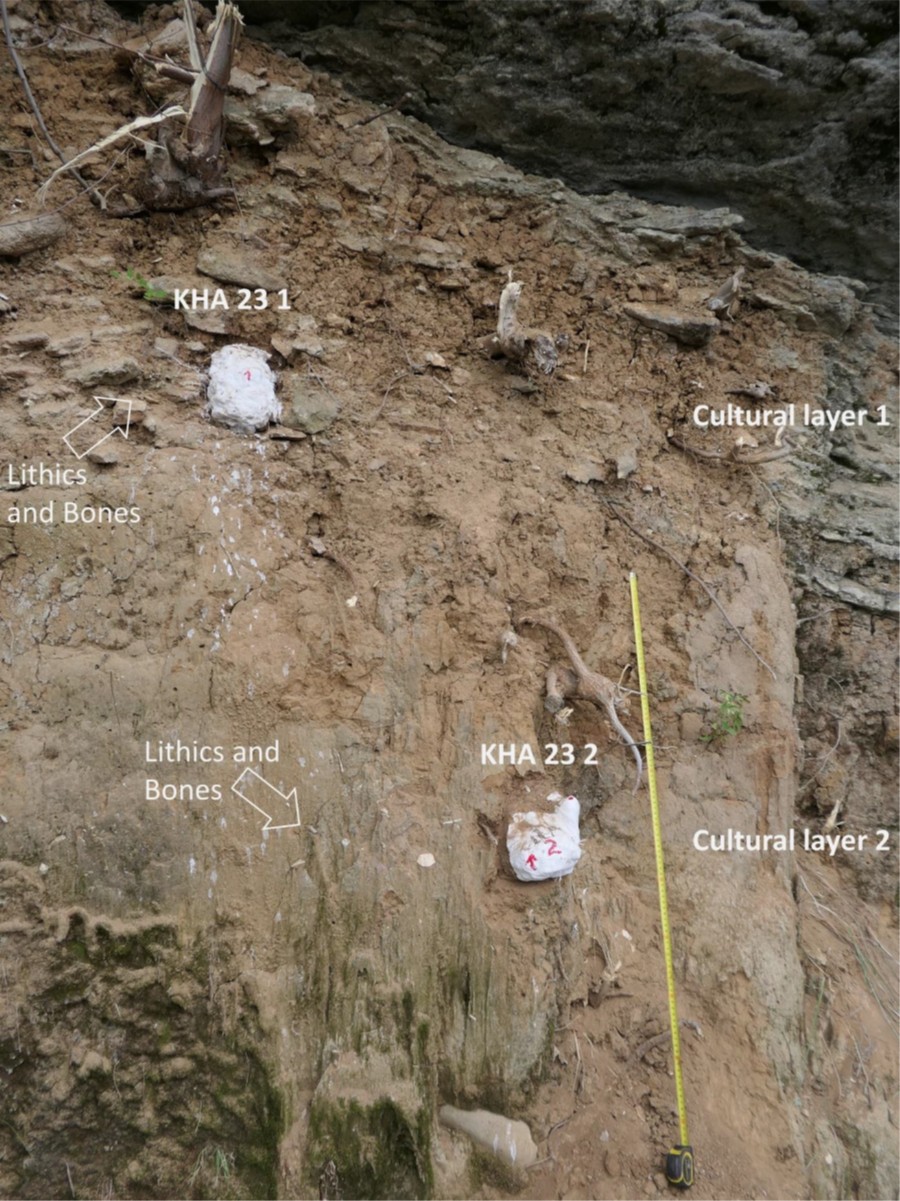

The site of Kharagauli is named after the closest town. It is located in the western part of Georgia, on the right bank of the River Chkherimela (N 42°01’43”E 43° 11’47”, elevation ~300 m above sea level) (Figure 1). The site is a remnant of a much larger cave that was destroyed during the construction of a new railway tunnel in 2018, when the site was first recognized. What remains is part of the deepest part of the cave, visible as a large patch (over 8 meters along the cliff face) of dark cave sediments against the light-coloured limestone cliff face.Initial work in 2019 revealed an exclusive Middle Paleolithic occupation. The deposits extend 2 meters deep into the cliff and are ~1.5 m-thick, with evidence for syn- and post-depositional geogenic and anthropogenic formation processes. This first season of excavations yielded some 400 lithic artifacts and ~300 faunal remains >1 cm.

The bones represent large and medium bodied herbivores (both cervids and bovids; Cervus elaphus, Megaloceros sp., Bison sp., Capra sp.), a feline carnivore (Panthera sp.) and a marten (Martes marten). These finding and the relatively high density of artifacts and bones are unusual for the region, as is the presence of only one cultural period. Work in 2019 identified two Middle Paleolithic units, based on the nature of the artifacts. There is also evidence for burning of both lithics and fauna.

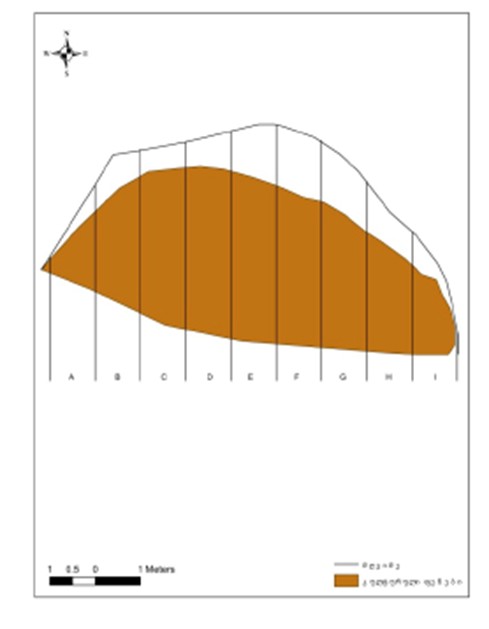

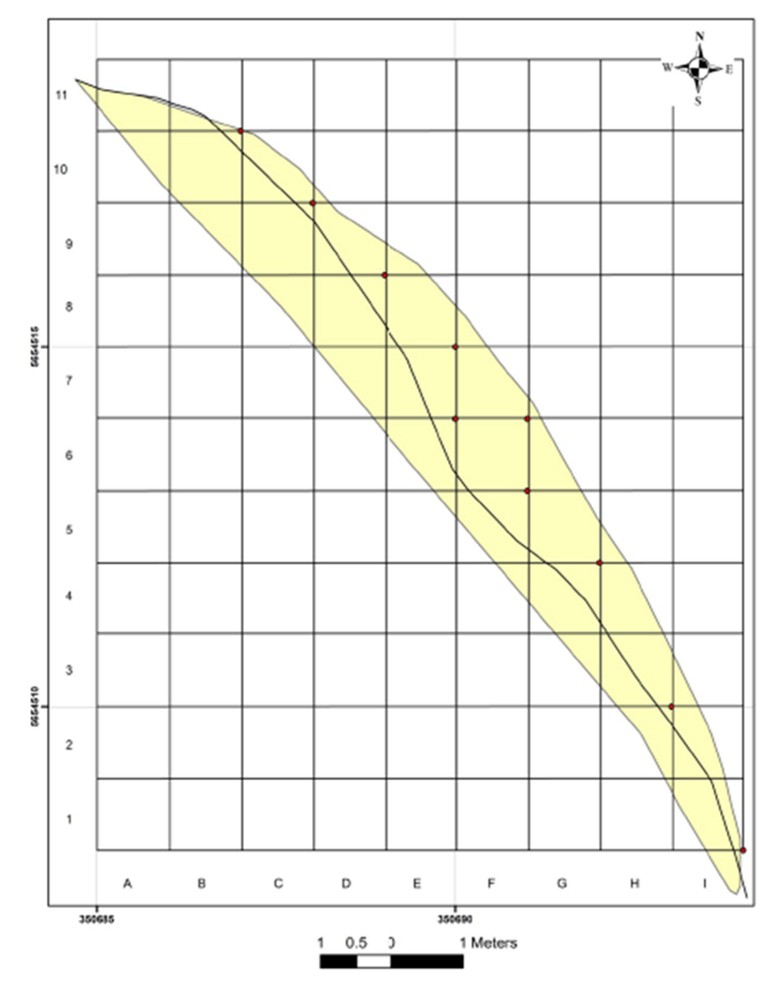

Figure 6. Map of the site showing its extent across the cliff face (E-W) and its depth (N-S). Anthropogenic sediments indicated in yellow. Bold line in the middle represented the projection of the bedrock roof

There are two clear sedimentary units in the site:

1. The top sediment complex consists of a reddish loam, disturbed by root penetration and other biological agents, relatively loose and coarse. The lower sediment complex contains sediments that are lighter in colour, appear to be more fine-grained and compact. At places they were very hard to excavate. In this lower complex we noted the appearance of sediment laminae, lenses of pebbles and more extensive horizon of such pebbles (Figure 7). Such horizons might suggest some fluvial activity within the cave, though the direct agent and processes involved could not be identified at this stage. One possibility is that the paleo-Chkherimela channel flowed at a higher elevation that its present course, and extensive floods occasionally penetrated all the way to the back of the cave. Given that the difference in elevation between the current riverbed and the cave floor is ~20-25 m, and that the distance would have been several tens of meters, this may not be a feasible explanation. Other mechanism for the depositions of the pebbles should be explored.

3. The amount of material collected from the lower complex is not sufficient to address the hypothesized cultural dichotomy (and possibly time differences) between the lower and upper sediment complexes. Regardless, our initial conclusion that the material is Middle Paleolithic remains valid.

4. Overall, several hundreds of lithic artifacts were retrieved. At this time, cleaning and sorting operations have not been finished so the exact number cannot be reported. The assemblage is mainly flake oriented, but some larger and more elongated pieces were also retrieved.

5. The artifacts collected from the site (mainly from the top sediment complex) are all made on flint. We noted several varieties of flint, the sources of which are not known at the moment. At least one of the raw materials seems to be a variety of red flint that is well represented in sites dated to the early phase of the Middle Paleolithic and is less represented in later Middle Paleolithic sites.

6. The frequency of retouched artifacts is relatively high. The retouch tends to be rather invasive. There is a clear dominance of pointed forms (retouched Mousterian points, convergent scrapers etc.) among the retouched items (Figure 8).

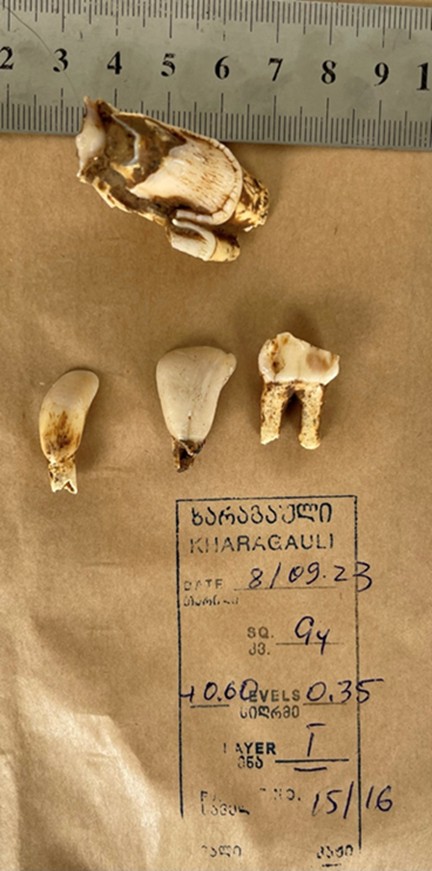

7. Faunal elements are fragmented. Fragment sizes vary between a few millimetres to several centimetres. The majority of pieces are fragmented long bones but there were also teeth, some metatarsal and metacarpal bones. Percussion marks were visible on many of the bones (figure 9). In most cases striation or cut marks could not be discerned due to the cemented carbonates adhering to the bone face. However, when visible, cut marks are clear, deeply incised (Figure 10).

Appendix

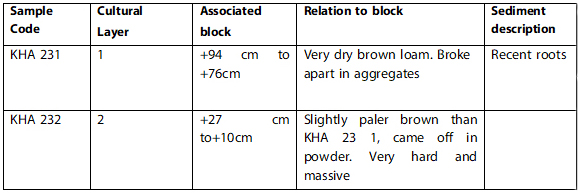

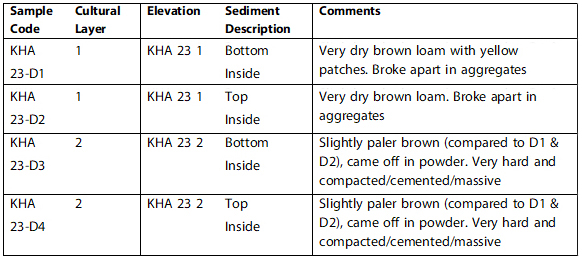

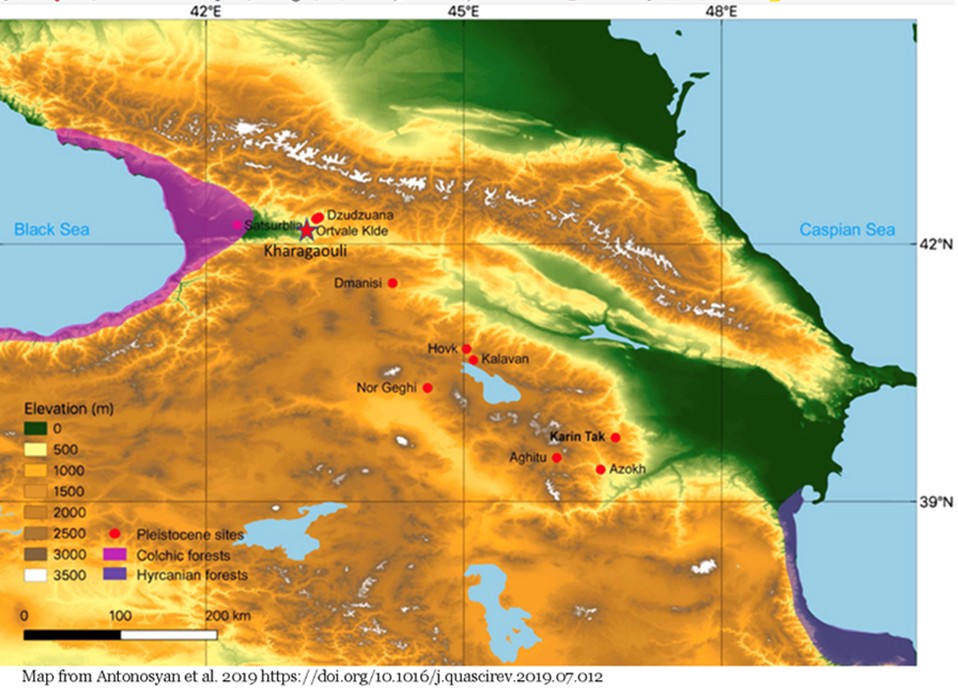

Sampling for Micromorphological and SedaDNA Analysis at Kharagauli Cave

By Mareike C Stahlschmidt and Thomas R. BeardWe visited the Middle Paleolithic site of Kharagauli on August 21st, 2023, and collected two block samples for micromorphological analysis and four respective bulk sediments for sedaDNA analysis from the two cultural layers. Kharagauli Cave is an artificially cut limestone cavity next to train tracks with a 1.5 m sequence of sediments preserved inside. The sediments consist of very dry, brown sandy loam with limestone gravel. Recent root activity can be observed throughout the profile. Two cultural layers were previously distinguished and were readily observable in the section as two distinct bands with lithic artefacts and bones. Block sample KHA 23 1 contains cultural layer 1 and block sample KHA 23 2 cultural layer 2 (Figure 1 and 2, Table 1). We measured the elevation of the block samples (top and bottom) from a defined point on the excavation balcony (Figure 3).